Clips for Laura Dennison

A collection of clips from San Diego Health, Healthy Kids, and other publications that capture some of my skills in reporting, shaping, and writing the kinds of materials I would take ownership of as a Senior Copywriter and Editor on your team.

Following In Her Father’s Footsteps

Hiking and medicine go hand-in-hand for Scripps' father-daughter doctor duo

For an entire decade, Prabhakar Tripuraneni, MD, a radiation oncologist at Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center and Scripps Clinic, drove past Torrey Pines on his daily commute without so much as a pit stop. That all changed when the Indian-born doctor and longtime Carmel Valley resident was invited on a hike. He was hooked. That walk among the stately trees and proud bluffs marked the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

For the past 25 years, Dr. Tripuraneni has been walking those same trails every Saturday and Sunday, plus twice more per week during the summer. He estimates he’s hiked there thousands of times.

He’s also taken on some notably tougher treks: Machu Picchu (“a walk in the park”), Mount Kilimanjaro (“a butt kicker”), Mount Whitney (three ascensions), and a 100-mile stretch of Spain’s Camino de Santiago. “I came to the painful conclusion the human body was not designed to hike 33 miles three days in a row,” he says.

Dr. Tripuraneni’s affinity for hiking has become a family affair. Much in the same way he encouraged his daughter Sravanthi to pursue a career in medicine, he also inspired her to follow in his footsteps on the trails. Sravanthi, now a family medicine physician at Scripps Clinic, Rancho Bernardo, has since tackled the Peruvian Andes as a team with her pop, and they are planning a hike along the coast of Portugal in April.

“He’s always out in front,” she says.

The second-generation Dr. Tripuraneni may also join her father in Iceland this summer (she hasn’t committed yet), and someday, she plans to make her own ascent of Mount Kilimanjaro. “His goal for me is to be able to hike for three hours or 10 miles, whichever comes first,” she says. Her father can hoof it for five hours, or nearly 20 miles.

And of course, she makes her own outings at Torrey Pines, where she keeps up her stamina.

“It must be something in our genes,” says the elder Dr. Tripuraneni. “My dad in India is 92. He walks a half mile in the morning and evening. All the younger guys who have retired are trying to keep up with him.

“I could play golf, too—but I’m a cheapo,” he adds. “Hiking is a physically and mentally healthy hobby that you can do for free anywhere in the world at any time of the day.”

Meet San Diego’s Surfing Spine Surgeon

For Scripps orthopedic surgeon Timothy Peppers, MD, surfing is a form of medicine

Before his day in surgery begins, Timothy Peppers, MD, a Scripps Clinic orthopedic spine surgeon at Scripps Memorial Hospital Encinitas, hoists his surfboard under his arm and treks down the bluff to beautiful Black’s Beach.

The powerful waves, the birds, the dolphins, the cliffs — everything about the tranquil setting makes it his favorite break.

“You feel like you’re getting away even though you’re still here in the city,” he says. “It’s a mini psychological vacation.”

From ocean waves to the operating room

As a La Jolla resident originally from Long Beach, donning a wetsuit and paddling out into waves up to twice his height has been his ritual for nearly 40 years — as a teenager, a construction worker, a med student, a father and now a surgeon.

“When you get out and surf in the morning, it sets the tone for everything that comes next,” Dr. Peppers says. “One good wave will make your day.”

Along the way, Dr. Peppers has taught his daughter, 14, and son, 9, to ride waves too. Though at the moment, he says, they’re crazier about another family hobby, skiing, as well as spending time skateboarding and rock climbing.

Staying active to stay in shape — and slow age-related aches and pains

At 55, the surgeon can appreciate what the surfing life has given him, and where it will take him yet. “One thing surfing does is keep you young,” he says. “I can see it in myself, and in my patients and friends who surf.”

Dr. Peppers emphasizes to his patients the importance of overall fitness in dealing with neck and back pain. “I spend a lot of my day trying to educate people. My active lifestyle — and love of surfing and skiing — has given me more insight to explain all these things.”

For a long time, he was driven to gain more experience and improve at his sport. “Now I just want to be able to keep going,” he says.

Many of Dr. Peppers’ patients are in a similar position while dealing with injuries: They want to stick with the activities they love.

“Most people don’t want to be told they can’t keep playing,” he says. “And I am one of those people, too. So I say, let’s figure out how you can stay on the golf course or tennis court as long as you can.”

Scripps Doc Off the Clock: Ni-Cheng Liang, MD

Dr. Liang has a special relationship with her patients—after all, she’s been in the same boat

While she was training to become a doctor, Ni-Cheng Liang, MD, learned all too well what it’s like to be a patient and a cancer survivor.

Dr. Liang, a Scripps-affiliated pulmonologist who specializes in integrative medicine, was in the second year of her fellowship in 2011 when she received the diagnosis: a particularly aggressive subtype of breast cancer, in stage 2.

In her early 30s at the time, Dr. Liang took a year off her fellowship to undergo chemotherapy and three surgeries. The procedures worked; today she’s cancer free. But there was an additional benefit — a profound connection with her patients, especially other cancer survivors.

“There is strength, connection and healing in sharing vulnerability,” she says. She calls it “reciprocal empathy.”

Blending the best of conventional and integrative medicine

The care Dr. Liang received is the same kind she practices: Integrative medicine, or the combination of conventional, evidence-based medicine with unconventional treatment, such as mindfulness, meditation, yoga and acupuncture.

“With everything I went through as a patient, I’m passionate about including integrative medicine in my practice,” she says. “It’s about augmenting allopathic medicine with a mind-body healing for a more holistic approach to patient care and well-being. It’s helped me get through and maximize my quality of life as a cancer survivor.”

She shares her own story with patients when she thinks it might help them endure tough treatments or the wait for test results.

“It helps to know someone else has gone through something very similar,” she says.

Connecting and competing with other cancer survivors

Her personal medical history has also connected her with other survivors in a very different setting. Dr. Liang, who emigrated from Taiwan to Maryland as a child, discovered in medical school her passion for the East Asian sport of dragon boat racing.

She picked up the paddle again last summer and joined Team Survivor Sea Dragons, which is composed entirely of cancer survivors. All 21 crew members must work in unison to paddle the boat.

“It takes a lot of core and upper extremity strength,” says Dr. Liang, who is also a keen stand-up paddleboarder.

She often practices with her team at Youth Aquatic Center on Fiesta Island three days a week as they hone their skills for the San Diego International Dragon Boat Race, a competition held each fall in Mission Bay.

“There’s a lot of endurance and stamina required, but it’s really motivating because there are so many survival stories in there.”

Cycling Team Fosters Fitness and Fellowship

Meet four members of “Team Doctor,” a decades-old cycling group at Scripps Health in San Diego

Just about every Saturday, the members of self-styled Team Doctor don helmets and spandex and hit the asphalt.

Despite the name, some are nurses, some work in IT. Whatever their job title, each rider is on the same trek: pedaling 30 to 70 miles around Carlsbad and La Jolla. This informal band usually numbers between five and eight cyclists who range in age from 50 to 74. After the ride, they grab breakfast together — a tradition going on three decades and counting.

“It’s just about hanging with your friends and exercising yourself into the ground,” says founder Douglas Fenton, MD, an OB-GYN at Scripps Coastal Medical Center Encinitas. “It was a way for people who love cycling to get together and ride hard.”

Fun, fitness and friendship

“Having a group of people makes it a lot more fun and easier to stay motivated to get out there,” says Jim Groth, MD, a family medicine physician at Scripps Coastal Medical Center Oceanside. He joined the cycling enthusiasts 15 years — and tens of thousands of miles — ago.

“The group has gotten pretty close socially, too,” adds Dr. Groth. “It’s a great bunch of people.”

Already a tennis player and runner, Mike Devereaux, MD, an internal medicine physician at Scripps Coastal Medical Center Hillcrest, added cycling to the mix in his mid-40s. Even as an occasional member of Team Doctor, he welcomes the lengths they go to.

“It promotes camaraderie and friendship,” he says. “They’re generally noncompetitive, but at times people push one another to achieve maximal fitness.”

“The team has provided a lot of bonding and emotional support,” agrees Gerard Lumkong, MD, a family medicine physician at Scripps Coastal Medical Center Encinitas. A former competitive cyclist, Dr. Lumkong was drafted by Team Doctor nearly 20 years ago.

“We talk some shop, but mostly keep it outside of medicine,” he says. “We have great conversations.”

Building stamina while banishing stress

Those who pedal faster wait up for others at predetermined checkpoints, allowing for group rides even when work, family, or injury has kept riders off the saddle. But training hard is a must for anyone attending their summer cycling getaways to Mammoth or the Rocky Mountains, which began 15 years ago. Neither snow nor cold stops them from tackling rides like Pikes Peak Highway: a 19-mile road climbing to the mountain’s 14,000-foot summit.

More valuable than the breakfasts and the bonhomie are the miles traveled. There’s no room on a bike for everyday stressors.

“You’re really divorced from all the social media and negativity,” Dr. Fenton says. “There’s just the sunshine and wind in your face.”

Understanding the Dangers of Vaping

Get the facts about e-cigarettes and learn why vaping is just as harmful as smoking

Studies show that electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are popular among teens, and are the most commonly used form of tobacco among youth in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2018 more than 3.6 million U.S. middle and high school students used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days — 4.9% of middle school students and 20.8% of high school students.

Vaping, or inhaling the vapor produced by e-cigarettes, vape pens or other battery-powered smoking devices, is not just a growing trend among teens. Adults have also taken up nicotine vaping, sometimes with the incorrect assumption that it’s healthier than tobacco. While nicotine certainly poses heightened risks to young people, it’s highly addictive and unhealthy at any age.

Jacqueline Chang, MD, a Scripps Clinic pulmonologist, and Brian Scull, MD, a pediatrician at Scripps Coastal Medical Center Hillcrest, explain the risks by answering several frequently asked questions about vaping.

Are all vape devices the same?

Vape devices may look like a USB flash drive, a pen, a little box or a miniature hookah. And whether you call it a vaporizer, vape or e-cigarette, they all do the same thing: vaporize a solution generally containing nicotine, as well as flavorings and/or other chemicals.

Is vaping better than smoking?

Vaping lacks the tar and some other components of cigarette smoke. That doesn’t mean it’s necessarily safer, though. Nicotine is dangerous on its own and makes vaping highly addictive, Dr. Chang says. Vape liquids usually contain a host of additives with their own significant and often unknown risks.

“There’s no standardization in the amount of nicotine, and no accountability of what’s in these additives and flavors,” says Dr. Chang. “We know some byproducts of these chemicals, one of which is formaldehyde, can be very bad. And nicotine is likely the reason smoking is linked to many kinds of vascular disease, heart disease, stroke and increased blood pressure. It can have effects on the body’s whole vasculature.”

Does vaping help to quit smoking?

No—in fact, the opposite may be true. “Most studies show it’s not more effective than other methods to stop smoking, and the nicotine could actually worsen addiction,” Dr. Chang says.

Is vaping regulated by the FDA?

No. The only regulated aspect of vaping is the marketing. The FDA doesn’t regulate what’s in vaping devices. It does not mean they’re safe, approved or standardized.

What are the dangers of vaping for young people?

Like smoking cigarettes, vaping is harmful from the prenatal stage on.

“Negative effects of nicotine have been noticed in the nervous system of developing fetuses, children and young adults up to 25 years,” Dr. Scull says. “It’s associated with sudden infant death syndrome, has a negative impact on learning, memory and attention, and increases health problems later in life.”

Kids who vape are also more likely to smoke. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, early evidence suggests e-cigarette use may serve as an introductory product for preteens and teens who then go on to use other tobacco products, including traditional cigarettes. One study showed that students who had used e-cigarettes by the time they started 9th grade were more likely than others to start smoking cigarettes and other smokable tobacco products within the next year.

How Tattoo Removal Works

Today’s laser tattoo removal techniques are quicker and more effective than ever before

That tribal tiger tattoo seemed like a good idea once upon a time, but now when you look in the mirror, you can’t help feeling buyer’s remorse. Fortunately, tattoo removal has come a long way in recent years.

Newer, more powerful lasers do a more effective job at breaking up ink particles so the body can flush them out. It takes fewer and shorter sessions now, too, says E. Victor Ross, MD, director of laser and cosmetic dermatology at Scripps Clinic in San Diego.

How are tattoos removed?

A laser beam about a half inch in diameter trained on the unwanted tattoo heats up the ink — but not the surrounding skin — so it breaks down the pigment, according to Dr. Ross, who has been removing tattoos since 1994.

Dr. Ross and his colleagues latest use powerful, versatile lasers to safely and effectively removes tattoos from the skin without harsh cutting, bleaching or abrasion.

How long does tattoo removal take?

“The actual time the laser is used is pretty darn short,” Dr. Ross says — under five minutes for a tattoo the size of a notecard. Including anesthesia and a consultation from the doctor, patients are often out the door in 15 minutes.

Here’s the catch: Several sessions are required — usually somewhere between four and 30. Bigger, newer tattoos and those with more ink require more sessions.

Does tattoo removal hurt?

Local anesthetic is usually injected for the procedure; the bigger the tattoo, the more numbing needed.

Does tattoo removal work?

Some tattoos can be completely removed, while others can be significantly lightened. Your dermatologist should consult with you prior to beginning treatment to let you know what to expect from treatment and how many treatments you may need.

“Black we can always remove,” Dr. Ross says. “Other colors don’t do as well, particularly colors like orange, green, blue and purple.”

One other caveat: Tattoos on the legs, especially the feet and ankles, have worse removal results. If the dermatologist isn’t entirely sure how effective the removal might be, or the patient isn’t sure they’ll be happy with the result, the doctor can test the procedure on a discreet area.

How quickly does the skin heal after laser tattoo removal?

“It’s normally an easy recovery,” Dr. Ross says. “There’s no lingering pain.” The skin will turn crusty for about a week, then return to normal. Afterward, the skin can even be re-tattooed — hopefully with results you’ll be happy with permanently.

Head Game: Blanca’s Story

Concussions can leave a lasting impact on young athletes’ lives, but Rady Children’s is helping kids get back in the game

Toward the end of the soccer game’s first half, Blanca Salas made her move. High Tech High School’s varsity team was leading Hoover High 1–0. Trying to protect that lead, the 15-year-old charged toward her rivals as they drove the ball closer to the goal. But players soon jumbled around and a melee ensued. An opponent bumped Blanca’s teammate, who in turn inadvertently shoved her to the ground. She hit face first.

Blanca briefly lost consciousness, but the match continued around her. “There was so much going on; no one could see me,” says the Barrio Logan resident. “The refs never realized I was on the ground.” About a minute later she picked herself up and got back in the game, but something was off. The ball came to her, and she remembers her teammates yelling to kick the ball away from their goal. “I didn’t know what I was doing. Finally I realized I was playing soccer and kicked it out,” she says.

Her head quickly began hurting so much she had to sit on the bench. She explained what happened to a trainer, who gave her a bag of ice—though it felt like the ice and the sunshine were worsening the pain. Eventually it went away. She stayed for the end of the game and went home feeling fine. However, at school the next morning Blanca began to feel dizzy, lightheaded and sensitive to noise. About a month before, a friend had suffered a concussion, so she figured she had, too. Blanca’s mom, Diana, picked her up and took her to the Sam S. and Rose Stein Emergency Care Center at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego, where her suspicion was confirmed.

A Common Injury—but Difficult to Diagnose

Blanca became one of the more than 500,000 American children who visit an emergency department for traumatic brain injuries each year, according to figures cited by the Weill Cornell Concussion and Brain Injury Clinic. A concussion is actually a form of traumatic brain injury, and three out of five of those kids suffered a concussion while playing sports. Perhaps surprisingly, girls’ soccer has the highest rate of concussions per capita among all youth sports (three times as many as boys’ soccer). Football is a distant second, according to a recent study by Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine.

A separate study found that nine high school sports accounted for 2.2 million concussions between 2005 and 2015. Blows to the head are the number one incident that sends adolescents to the ED, and the leading cause of disability and death in American children, particularly in the age groups of 0–4 and 15–19, notes the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

These studies come on the heels of increased scrutiny on concussions suffered by professional football players. But as evidenced by Blanca and the half million other kids who end up in the ER each year, it’s not only the pros who are at risk. Kids are actually more likely than adults to suffer traumatic brain injuries, because their bodies aren’t fully grown. “When you’re little, your neck is weaker,” says Pritha Dalal, M.D., a physician at Rady Children’s specializing in physical medicine and rehabilitation. That allows the brain to more easily impact the inside of the skull or undergo a twisting motion, both of which lead to concussions.

Unlike cuts or broken bones, concussions can be extremely hard to diagnose, and just 10 percent of them cause loss of consciousness. Concussions can even result from a blow to the body followed by an impact to the head. The vast majority of concussions are not life threatening, but even mild ones can cause prolonged problems. Beyond physical pain like headaches, symptoms can include cognitive, sleep, mood and balance issues. Up to 30 percent of concussed high school athletes can experience symptoms for more than six weeks, according to the Concussion Legacy Foundation.

Symptoms also can take days, weeks or months to appear, so it’s tricky to know when kids are ready to return to school, sports and other daily activities. “Concussions can vary, anywhere from no symptoms whatsoever, to short-term memory or behavioral changes, headaches, nausea, vomiting or vertigo,” says Michael Levy, M.D., Ph.D., head of pediatric neurosurgery at Rady Children’s and former sideline head injury consultant for the NFL.

After a first concussion, kids are up to six times as likely to suffer subsequent and more severe concussions, so returning to play at the right speed is imperative. And too little mental rest—or possibly too much screen time— can drastically prolong the recovery period. “Concussions always resolve over time,” says Dr. Levy, “but you need to protect the athlete in the interim so they don’t reinjure themselves while in a vulnerable state.”

Getting Patients to a Specialist Faster Makes a Big Difference

Rady Children’s has overhauled its concussion treatment process, from diagnosis to the moment the patient is allowed back on the field. Experts treat all forms of pediatric traumatic brain injury, and one team specializes in concussions suffered by youth athletes.

Rady Children’s concussion clinic is part of the Division of Orthopedics & Scoliosis, which is ranked seventh in the country by U.S. News & World Report. The staff of the Hospital’s 360 Sports Medicine program are trained to make advanced diagnoses and rehabilitate patients to reduce pain, strengthen key muscles and get back into a jersey. Since impaired balance is a common symptom that can linger for months, they’ve also created one of just a handful of pediatric balance and vestibular programs in the world. Many patients who suffer a concussion first go to a school nurse or their primary care physician rather than an emergency room. That’s why Rady Children’s involvement extends to schools.

They’ve pioneered a medical information system to keep primary care doctors updated on the latest guidelines and recommendations—which is particularly important considering that Rady Children’s network spans such a large region.

“We have figured out a better way to make it easy for pediatricians to understand the best ways to treat them,” Dr. Dalal says.

Some of those guidelines pertain to when a doctor should send their patient to a specialist. If a specialist is not needed, it’s better not to waste anyone’s time. Conversely, when a patient needs to see a neurologist, they should do so right away. For that reason, Rady Children’s has created an expedited track for referring patients to specialists, often in just a few days.

“We put pathways in place to have a patient seen quickly, so they can be diagnosed and start treatment quickly, and begin getting back to their activities,” Dr. Dalal says.

Recovery Means Resting Both Body and Mind

Doctors told Blanca to stay off the soccer field for a while. “I was kind of freaking out because I felt like I couldn’t do anything,” she says.

Though she didn’t have to take any days off school, returning to her studies wasn’t a simple process. Following a concussion, patients must return to schoolwork carefully and avoid screens. Limiting computer time was difficult for the High Tech High student, who does most of her work that way, but her teachers were able to switch some assignments to paper so she wouldn’t fall behind.

Initially, Blanca’s return to schoolwork ate into her sleep time. Adequate shut-eye is crucial to recovery as well, so her doctors urged her to get extensions on assignments and maintain seven to 10 hours a night. “Getting kids back to school safely and in a way that’s accommodating and not stressful is very important. It’s a key aspect of what we focus on,” Dr. Dalal says.

Blanca was experiencing headaches, and her balance was out of whack. “I’d think I was standing still and everybody would be like, ‘You’re ,’” she says. During a concussion, the inner ear’s mechanism for maintaining the body’s orientational awareness can be thrown off, causing dizziness and imbalance. The neuroscientists at 360 Sports Medicine’s balance and vestibular lab can test patients for precise diagnoses, which physical therapists can then use to create treatment programs. Blanca’s team prescribed neck-strengthening and other exercises. After six months of “wobbling,” as she calls it, she finally regained her equilibrium.

In the past, doctors believed getting ample physical rest was the most critical measure for healing concussions. “The brain is the only organ that truly needs sleep, so adequate rest is imperative,” says Andrew Skalsky, M.D., director of Rehabilitative Medicine at Rady Children’s. “But kids need to resume normal social and physical activities that aren’t at risk for repeated concussion in order to avoid mental health conditions, such as depression or anxiety, that may follow from being socially withdrawn. The newest recommendations are to rest for a short period, then start doing more as you feel better, as long as symptoms aren’t becoming worse.”

The consensus has likewise evolved about resting the mind. “They used to believe you didn’t need cognitive rest, but it turns out that’s not the case,” Dr. Levy says. “So we work with schools to make sure kids are integrated back properly.”

Blanca’s return to soccer began with a few weeks of daily 20-minute walks. Eventually she ramped those up to jogs, which at first she could do for only five minutes without headaches. After a while, she was allowed to do warmups and some ball drills at soccer practice. (Blanca plays club soccer, so her competitive year stretches through the summer.)

She eventually got the okay to play a bit more aggressively, but at one point she bumped into a teammate and her headaches worsened, so she had to dial back the intensity. “It was really hard for me to realize I couldn’t give it 100 percent. I wanted to go for it and be around my teammates, but I had to go really slowly.” Blanca’s doctors think she may finally be ready to play soccer full steam when school starts up again this fall.

Published in the Fall 2018 edition of Healthy Kids Magazine

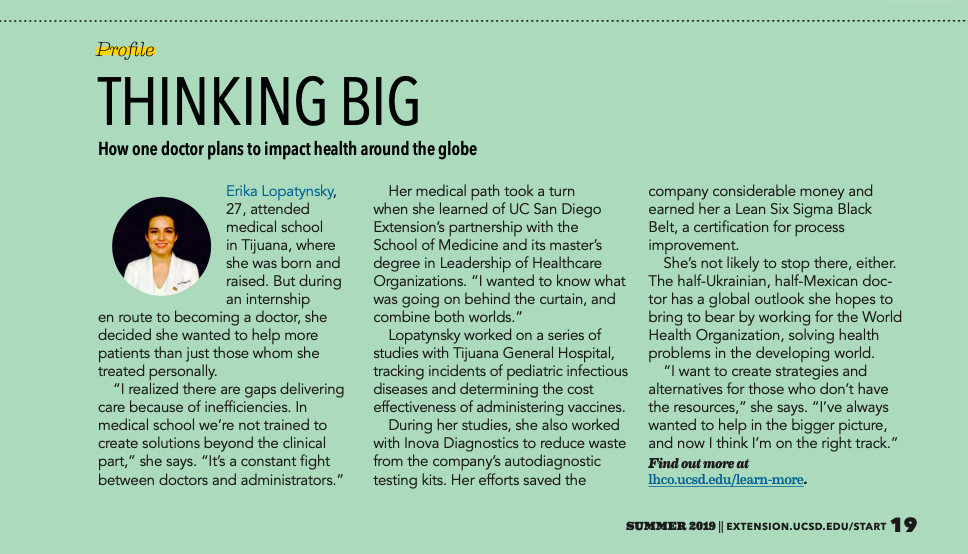

THINKING BIG

How one doctor plans to impact health around the globe

Erika Lopatynsky, 27, attended medical school in Tijuana, where she was born and raised. But during an internship en route to becoming a doctor, she decided she wanted to help more patients than just those whom she treated personally.

“I realized there are gaps delivering care because of inefficiencies. In medical school we’re not trained to create solutions beyond the clinical part,” she says. “It’s a constant fight between doctors and administrators.”

Her medical path took a turn when she learned of UC San Diego Extension’s partnership with the School of Medicine and its master’s degree in Leadership of Healthcare Organizations. “I wanted to know what was going on behind the curtain, and combine both worlds.”

Lopatynsky worked on a series of studies with Tijuana General Hospital, tracking incidents of pediatric infectious diseases and determining the cost effectiveness of administering vaccines.

During her studies, she also worked with Inova Diagnostics to reduce waste from the company’s autodiagnostic testing kits. Her efforts saved the company considerable money and earned her a Lean Six Sigma Black Belt, a certification for process improvement.

She’s not likely to stop there, either. The half-Ukrainian, half-Mexican doc- tor has a global outlook she hopes to bring to bear by working for the World Health Organization, solving health problems in the developing world.

“I want to create strategies and alternatives for those who don’t have the resources,” she says. “I’ve always wanted to help in the bigger picture, and now I think I’m on the right track.”

Find out more at lhco.ucsd.edu/learn-more.

Social media post

It sounds almost too good to be true: Physicians are winning the war on cancer. Remarkably, cancer death rates in humans have dropped 27 percent over the last two decades. More people are surviving the disease thanks to prevention, improved treatments, and earlier detection through screening. Powered by next-generation sequencing, newly developed multi-cancer early detection (MCED) tests can now screen for numerous cancer types with a simple blood draw.

⠀

Major veterinary organizations have deemed early detection critical for management of cancer in companion animals, too. Survival rates are highest with early diagnosis. Unfortunately, canine cancer is usually found in late stages, mainly following the onset of clinical signs.

⠀

But now, like physicians, veterinarians are finally equipped to screen for cancer in dogs. The use of MCED tests in high-risk patients could lead to earlier diagnosis, before clinical signs appear. Powered by next-generation sequencing just like the MCED tests for human patients, OncoK9® – The Liquid Biopsy Test for Dogs™ is demonstrated to detect 30 different types of canine cancer.

⠀

More people than ever are surviving cancer thanks to effective screening programs. Let’s make that possible for dogs, too.

As a paleoclimatology researcher and science envoy for the US State Department, Leinen has been virtually everywhere—on land and sea. She’s visited most of the world’s nations, setting foot on all seven continents, a dizzying array of Pacific islands, and the South Pole. That doesn’t even cover her time crisscrossing the world’s oceans, on the surface and the seafloor, where she’s ventured as deep as 13,000 feet and once discovered undersea hydrothermal vents 250 miles off the Washington coast.

Social media post

Our ears perked up last summer when @sandiegomag put out a call for nominees to Celebrating Women 2022, a recognition of women who were “transforming San Diego and the world!” Among the many incredible women we know doing incredible things, our Chief Medical Officer, Andi Flory, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology) sprang to mind. The magazine’s description of the “changemakers, groundbreakers, and visionaries” they sought to honor spurred us to toss one of Dr. Flory’s many hats—veterinary oncologist, startup founder, mother, pet parent—into the ring.

Inside an unremarkable office park in Rancho Bernardo, Chris Duffey, a middle-aged electrical engineer, powers up a gadget about the size of a coffee maker. With parts made from PVC pipe, copper wire, and aluminum foil, the contraption looks like a movie prop, something Marty McFly might stumble upon in Doc Brown’s lab.

Duffey cranks up the power source—wired to a knob housed in an Altoids tin—and the machine sputters to life with a staccato buzz. Just then, violet arcs of electricity emanate from an aluminum-foil-covered ring topping the device. He presents a normal fluorescent light bulb in his hand, and as he brings it within a foot or so of the gadget, the bulb illuminates. That’s the function of this homemade Tesla coil—it’s a rudimentary wireless power source.

“It’s been a while since I was able to build anything,” says Duffey, whose electric grin says he enjoys this more than his paperwork-heavy day job as an engineering director in Northrop Grumman’s autonomous systems division.

Social media post

Each year, cancer cuts short the lives of many dogs who might have enjoyed many more years with their families, had the disease been detected earlier. Poppy, the mixed-breed rescue shown here, was one of them. Just four when she lost her battle with late-stage pancreatic cancer, Poppy was a small pup who left an outsized legacy for dogs who came after her.

Her devastating fight with cancer inspired her human, Daniel Grosu, MD, MBA, to start PetDx together with a mission-driven team of scientists and veterinarians, with the aim of unleashing the power of genomics to improve pet health. Poppy’s memory lives on in those who loved her, in the story we’re sharing here, and in our laboratory: our most important instrument, a powerful DNA sequencer, bears her photo and goes by the name of “PoppySeq.” #NationalPetMemorialDay 🧬🐕🐾

Social media post

Bella presented at her routine wellness visit with no clinical signs of cancer, but due to her age and breed, was prescribed OncoK9. When the result came back as Cancer Signal Detected, a Confirmatory Cancer Evaluation was performed, revealing multiple concerning masses and lesions, leading to a diagnosis of hemangiosarcoma.

The result helped the veterinarian shorten the path to diagnosis, allowed Bella’s owners time to prepare and the option to start therapy, and allowed Bella to begin therapy prior to developing clinical signs—potentially giving her prolonged good quality of life.

Social media post

In one sense, the story of PetDx® begins down the road at @illuminainc, where President and CEO Dr. Daniel Grosu served as the very first chief medical officer. In another sense, it begins with Poppy. After stealing Grosu’s heart, the 8-pound rescue dog battled pancreatic cancer. Though she lost that battle at the young age of four, she inspired Grosu to leverage Illumina’s next-generation sequencing technology to develop noninvasive cancer testing solutions for pets.

“People really care about their pets, and we can help make a big impact in the lives of many families,” says Grosu. “Because when a pet has cancer, it’s not just the pet that’s suffering. It’s really the entire family that’s suffering.”

He is tall and slender, with light brown hair that forms a small wave. In his London accent, he draws out vowels, particularly when he says viiiruses. He is a trained opera singer who practices tap dance and the waltz during otherwise wasted minutes of laboratory life, like waiting for a centrifuge to stop spinning. In and out of the lab, he wears V-neck sweaters, skinny jeans, and stubble, an unassuming uniform for someone who spies on nature’s conspiracies to unleash a plague on New York.

…

Standing by the centrifuge, there is nothing to do but wait. Moments like that are when he waltzed while earning his doctorate. And he might do a few steps in the BL3, too, but it is nearing the end of a long day, during which he has zipped up the stairs between the lab’s floors many times. His stubbly face looks weary through the helmet, slightly crooked on his head. Inside the respirator mask, a tiny lightbulb (indicating that the electric filter is on) gives his face a blue cast. When he speaks, his voice sounds like he’s talking into a bucket. “I spend half my life writing on tubes and waiting by centrifuges,” he says.

…

And as is often the case, he found mysterious genetic sequences—”dark matter”—that don’t fit with any known life-form. About a third of the genetic codes he finds are dark matter, unidentifiable shadows at the edge of scientific knowledge. “It may be rubbish; it may be bacteria,” he says. “It could be anything.”

…

Just the other day, he was opening a bank account at a Chase on Ninth Avenue in midtown. The banker offhandedly asked, “What do you do?” When he told her, she wrote her phone number on a piece of paper, handed it to him, and said: “Give me a call when you find something serious. I want to be the first to know.”